Value-based marketing is a relatively new model for emerging brands entering a landscape saturated by conscious consumers – with many valuing environmental impact and transparency over trends. And as new brands go to market, carefully crafting their products + communications to avoid accusations of greenwashing or otherwise being viewed as performative in their efforts to reduce, or preferably reverse, the environmental impact of their products, the reality is that Patagonia has been writing the script for impact-driven brands since far before sustainability in consumer goods was a thing.

As the company prepares to enter its 50th year, and founder Yvon Chouinard signs the company over to mother earth, there are a few pillars to Patagonia’s DNA that have allowed it to not only sustain itself as one of the most recognizable brands in the world but sustain the world itself in the process.

In their own words, Patagonia’s core values are:

In signing Patagonia over to the Patagonia Purpose Trust, 100% of the company’s non-voting stock will now go to a non-profit called The Holdfast Collective which will distribute all profits each year not reinvested into the business as a dividend to help support the climate crisis.

This move, while radical, is certainly not out of character for both Yvon, and by extension, Patagonia. Having emerged in 1973, these core values have been the guiding principles for everything the brand has done to date, and will likely continue to do. They are arguably the foundation of the brand’s success, and despite having a reputation for being something of a bougie outdoor brand in recent years, it is these values and virtues of putting the environment first that allowed them to, in turn, put product + values first in their business decisions to achieve notoriety for their products — even if you don’t fancy climbing rocks.

We’ve performed a study of not only Patagonia’s core values, but their history as a brand, and have distilled each of the decisions that they’ve made over the year into their core values, and by extension the impact that those decisions have had, to provide a look into the teachings that Patagonia’s value-based model has to offer us.

1950 – Yvon Chouinard starts making pitons in his parents’ backyard.

While Patagonia as a brand wouldn’t exist for 13 years from the time that Yvon began producing pitons (climbing spikes climbers used to use to drive into the climbing surface to use as an anchor), it is still indicative of the values that would come in the realization of Patagonia some years later.

While it’s commonplace now to hear about a brand starting in the basement or backyard of the founders’ parents, this was far from the case in 1950 and definitely broke the conventional norms of the time as Yvon set out to fill a niche need for a niche sport in a manner that was sustainable and with little waste.

Though pitons would later become obsolete and replaced by equipment that didn’t cause permanent damage to climbing surfaces, they were, at the time, a standard piece of equipment — so no points here for unnecessary damage or protecting nature, but no shade either.

Editors Note: Startup founders who are reading this, take note of Yvon’s decision to launch with a single product of impeccable quality. Just saying.

1965 – Chouinard Equipment started with Tom Frost – Becomes the largest supplier of climbing equipment in the US

Partnering with a fellow climber, Yvon collaborated with Tom Frost in order to begin creating and manufacturing climbing equipment for an ascent of Kat Pinnacle — ultimately leading to the creation of Chouinard Equipment.

In addition to refining the pitons Yvon had previously been manufacturing, ultimately coming to fruition in the form of the Realized Ultimate Reality Piton, the pair focused on refining existing equipment and finding solutions to issues faced by climbers through the invention of new pieces.

This focus on quality, and of course the shedding of any conventional restrictions, ultimately garnered them recognition within the then budding climbing community — allowing them to quickly become the largest supplier of climbing equipment in the US.

Editors Note Again: Stages of a startup when?

1973 – Introduces Rugby shirts and a small outdoor apparel collection.

It’s 1973 and you’re the largest supplier of climbing equipment in the US, what do you do? Obviously, you start making Rugby shirts, because why not?

While it is still unclear why Chouinard made the decision to make Rugby shirts instead of climbing apparel, it’s anything but conventional, and as per usual they were of the finest quality and became a staple in many a climbers’ closet — and to this day are highly sought after vintage pieces for those in the streetwear community. Quality always wins.

1981 – Developed Synchilla (Synthetic Chincilla) fabric and Retro-x fleece pullover.

1981 saw the first action taken by Patagonia that encompassed each of the businesses’ four core values with the release of the Retro-x fleece pullover (a similarly collectible and sought-after piece by vintage clothing and streetwear enthusiasts) — a garment that recycles 25 plastic bottles per piece made.

At a baseline, the concept of the Synchilla Retro-x fleece pullover, possibly the first mass-market instance of upcycling practices, was the first major step for Patagonia in exercising their ability to not only avoid environmental impact through the production of their products but negate some damage already caused through the production of commercial plastics.

The product itself introduced the bold colorways and patterns that would become synonymous with the Patagonia brand, and a staple of their product offering that is still represented to this day.

Sometimes you release a sweater, sometimes you release a revolution.

1984 – Patagonia opens an on-site cafeteria offering “healthy, mostly vegetarian food,” and child care services.

Yet another staple of modern office culture that Patagonia was implementing far ahead of the times most likely simply as a way of making a commitment to the physical and mental wellbeing of the company’s workers by ensuring that meal options weren’t limited to whatever they were able to bring in each day, or whichever quick meal was within the closest proximity to the office.

While broadcasting these practices to attract new and competitive talent was not yet the staple operation in business that it is now, it likely lead to higher productivity within the workforce (a word Chouinard likely seldom used) and a higher quality of life due to the relief of stresses associated with the cost and maintenance of childcare and workday meals.

While not directly product related, this measure arguably contributes to the production of the best possible products, and with the focus on veggie options and the wellbeing of the staff, there’s an argument to be made for not causing unnecessary harm.

1985 (or 1986 depending on where you look) – 1% for the planet.

Though the eponymous organization wasn’t founded until 2002 to prevent “greenwashing”, a word that likely wasn’t coined until around the same time, the practice of allocating and donating 1% of sales, or 10% of profits (whichever was greater) to the environment.

While not product driven, the program was radically structured to fund workers who were building or working on local environmentally driven projects in order to allow them to do so full time — something that was otherwise unthinkable then and would be arguably unspeakable still to this day for most organizations.

To say that this initiative wasn’t radical would be an understatement, though it is deeply rooted in the company’s values in its efforts to help the environment while actively seeking to relocate existing staff to other projects that do not immediately serve their product.

Fast forward to 2018, and Patagonia would expand on this work by developing Action Works, an organization dedicated to connecting people on a regional level to impact-driven programs, as well as training activists – consistency is key.

1996 – Patagonia pledges to use all organic cotton (plus a few honorable mentions).

The incorporation of organic cotton into Patagonia’s products was a first for some of their more radical business practices and set the pace for a number of future instances of course correction as a means of maintaining their values.

In the modern climate of cancel culture, brands are often not given a second chance when caught up in any sort of controversy (particularly true of emerging brands over legacy ones), but Patagonia has continuously set a prime example for how to not only make mistakes but remedy them in a meaningful way in order to not lose the trust and confidence of their community.

In the early 90s, Patagonia did an audit of their environmental impact which found that their cotton production left a significant environmental footprint — something that is fairly well documented today.

As a response, rather than doubling down or denying its missteps, the company simply took account of its mistakes and quickly switched to organic cotton to significantly reduce its footprint as a result of its production process.

From an optics perspective, this illustrated through action to their audience that they were both capable of recognizing their mistakes, but also true to their values and commitment to both the quality of their products and the impact that they, and by extension, their customers, have on the world.

The company would repeat this same behavior in 2005 when criticized by PETA due to the practice of mulesing at the farms where the brand was sourcing its wool — a practice that is contentious and seen as cruel by some groups of people.

Once again, as a response, Patagonia gracefully accepted criticism and began sourcing their wool from the South American cooperative Ovis 21, which later fell under scrutiny from PETA after a video surfaced of the cruel treatment of animals at their facilities in 2015 which prompted Patagonia to pull their sourcing from them, this time taking things a step further and releasing a guide for the treatment of animals, land-use practices, and sustainability standards in 2016 for which all of their material sources would have to meet in order to work with them.

Radical.

2010 – Sustainable Apparel Coalition was formed to enable brands to track social and environmental impacts.

The forming of the Sustainable Apparel Coalition signaled a shift of Patagonia sending their gaze outward to impact not only their own products and practices but to make an industry-wide impact through the implementation of the tools created for the coalition.

Though the brand had been an industry leader in ethical and environmentally conscious business practices for a number of decades at this point in the brand’s lifecycle, the launch of the coalition not only provided Patagonia cross-brand recognition through alignment with the other members and brands utilizing the tools, but also set standards for what had previously been ambiguous or undefined metrics for sustainability so brands could not only identify and correct poor practices but be recognized and rewarded for their efforts — a sentiment that set the tone for the decade and has held true to today.

With over 150 current members, the coalition itself serves as a badge of honor for brands who are focused on and seek recognition for their values-based efforts towards sustainability and reducing environmental harm.

2011 – Patagonia launches the Common Threads Initiative.

We’ve covered growth loops extensively in our content, but this is the first time we’re talking about circular consumption — a practice that in the current landscape has become standardized but was not necessarily the norm in 2011.

The introduction of the Common Threads initiative was not only unconventional at the time but a testament to the quality of Patagonia’s products by virtue of the concept alone and the understanding that, for all intents and purposes, the shelf life of the clothing would always outpace the rate at which it needed to be recycled.

Rolling out the initiative not only encouraged the existing community to buy with less guilt, at a time when conscious consumerism was beginning to develop a foothold (climbing pun anyone?) in the consumer zeitgeist but was also able to leverage as a marketing chip as many of these initiatives have historically been.

While greenwashing and virtue signaling are both tactics in marketing, particularly as it comes to value-based marketing, that is typically recommended to be done with delicate intent so as to not be perceived as performative, or worse- an imposter, when your company fully embodies these virtues it becomes part of the brand DNA and immediately recognizable at a consumer level – leading to increased public trust and awareness.

Honorable Mention:

2012 – Patagonia becomes a Certified B Corporation.

2014 – Patagonia announces it is using 100% traceable down.

This seems to be an appropriate time to make a distinction for building the best product, as the previous actions taken with their wool sourcing and the switch to organic cotton were both driven by environmental impact, reduction of harm, and quality of product, but with no mention of cost.

To Chouinard’s dismay, the brand has been dubbed in recent history as “Patagucci” — primarily due to the brand’s somewhat aspirational price point.

And while this may be seen by many as irrelevant to, or even evidence against, their values-driven practices, the reality couldn’t be further from that as their price point is very much reflective of their values.

From a productive perspective, the focus on quality and sustainability does, to some degree, impact pricing since, as we all know, organic is always going to out-cost traditional sourcing — whether we’re speaking about food, clothing, or otherwise. This focus on sourcing drives up prices, which is often recognized by their community as a reflection of the quality of the garment that is being offered.

This same focus on quality also reflects back directly to their focus on harm reduction and protection of nature as inevitably with regard to environmental impact and footprint — more is more.

The practice of producing fewer garments of higher quality at a higher price point that will inevitably last longer leading to lower impact from production is a practice that is reflected in an ongoing paradigm shift in consumer behavior and one that has been encapsulated in the values of Patagonia from production to consumption.

2016 – Patagonia donates 100% of $10M in sales from Black Friday to environmental organizations.

Couldn’t make it through the history of Patagonia without mentioning the infamous “Don’t Buy This Jacket” ad in the New York Times that was published on black Friday.

While the brand didn’t pull all of its products from store shelves during the kickoff to the 2016 holiday buying season, it did give many shoppers reason to pause before making purchases, a strong push forward for their commitment to conscious consumerism.

In the ad, and the associated article published on their website, the brand recognized that while, yes, they were a company and companies were driven and relied upon sales, everything they do makes an impact on the environment — no matter how much care they take with their production.

2017 – Patagonia boycotts Outdoor Retailer trade show in Utah to protect federal land.

Cause No Unnecessary Harm

Use Business to Protect Nature

Not Bound by Convention

Politics aside, the boycott of the Outdoor Retailer trade show and lawsuit against the President was yet another set of acts on behalf of Patagonia that could arguably be seen as bad for business on paper — as they likely would otherwise do a lot of wholesale business while at the trade show, and as we all know lawsuits are expensive.

They did, however, choose to leverage the business in order to protect nature by leveraging not only their own funds for the lawsuit but by drawing public attention to the potential threat to the protected land by way of the boycott.

These actions are an incredible illustration of long-term thinking, in that they were likely detrimental financially to the business in the short-term, though resonated directly with the community that continuously supports Patagonia as a brand, and their commitment to the environment, promoting loyalty, advocacy, and retention for the brand.

2017 – Launch of Worn Wear Initiative – expanding circular commerce.

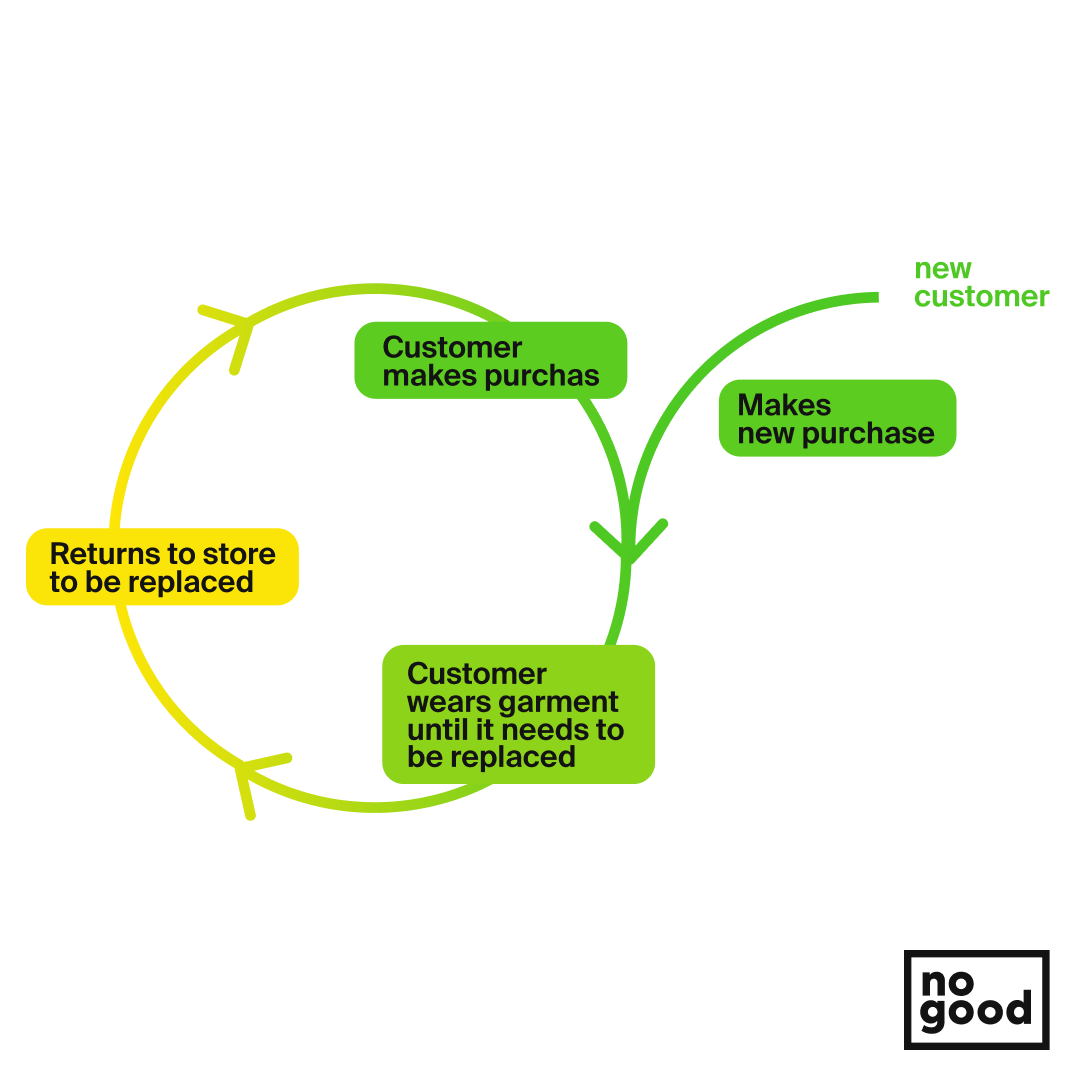

While the Common Threads Initiative was a big first step for Patagonia toward their circular commerce program, in 2017 Patagonia took things a step further in recognizing that while recycling does reduce waste, it also requires the process of breaking down existing garments to turn them into new ones – causing negative environmental impact in the process.

Once again defying growth norms with their approach to acquisition and retention, worn wear expanded the Patagonia community to reach new customers who may otherwise not be able to access their products due to the high price point that they carry as a result of their quality and focus on sustainability.

By allowing existing customers to have their garments repaired, which is yet another cost that Patagonia was willing to eat in pursuit of protecting the environment, they once again positioned themselves for loyalty and advocacy by encouraging their community to repair or recycle garments that they already owned, while simultaneously rewarding sustainable practices within their buying community by providing credits to those who traded in used garments to be sold or recycled.

While there is an argument to be made that some of these practices may directly hinder sales, as mentioned, they also expanded their community and resonated directly with those who had already built loyalty to the brand by supporting the expansion of their circular commerce program.

Honorable Mention:

2021 – Patagonia announced it would “not be bound by convention” and would close stores and give employees vacation from December 25 to January 2.

2022 – Patagonia makes Earth its only shareholder.

Build the Best Product

Cause No Unnecessary Harm

Use Business to Protect Nature

Not Bound by Convention

We may have covered this at the jump, but there’s something to be said about this decision through the lens of Patagonia’s core values.

While many may see this, and while similar historical decisions on behalf of the company may not have included building the best product as a core value associated with them – this time things are different.

Creating the Patagonia Purpose Trust encapsulates perfectly the essence of Patagonia’s DNA in their ability to not only produce the highest quality products but do so in a way that resonates directly with audiences and carefully navigate through the landscape of public and environmental advocacy to do the most good, as often as possible.

And while the product may not be at the center of these decisions as the brand pushes forward to set an example for what the future of business and brands may look like, by taking this step they are making the argument that there’s no longer separation between the building the best product and doing what’s best for the environment.

As communities and consumers continue to place heavier emphasis on impact and values as major contributors to purchasing decisions, the longevity and impact of a product will only add value to a brand, and their attempts and actions to lessen the impact and strengthen advocacy will yield only benefits.

What’s to come:

2025 – Carbon Neutral