As TikTok continues its takeover of the media landscape, with it comes the mass-adoption event of what has been deemed as the “authentic aesthetic”. With brands shifting preference to UGC over high-polish, high-production output, the age of content needing to be “Instagram-worthy” may quickly be seeing its last days.

The aesthetic of authenticity, however, is more than just a look, and as brands move to emulate the visual appeal that TikTok has built for itself, it’s important that the authenticity of content goes deeper than just surface level.

It should be no surprise that the authenticity aesthetic is just that — authentic. And so brands must carefully navigate their approach so as to not lose trust with communities by producing content with an aesthetic that is something it’s not.

What is the authentic aesthetic?

How it started

Authenticity is defined as something that is “genuine” or “true to its core values”, and while this may indicate that what is authentic may fluctuate and change from brand to brand or creator to creator, the root of the aesthetic is rooted in imperfection.

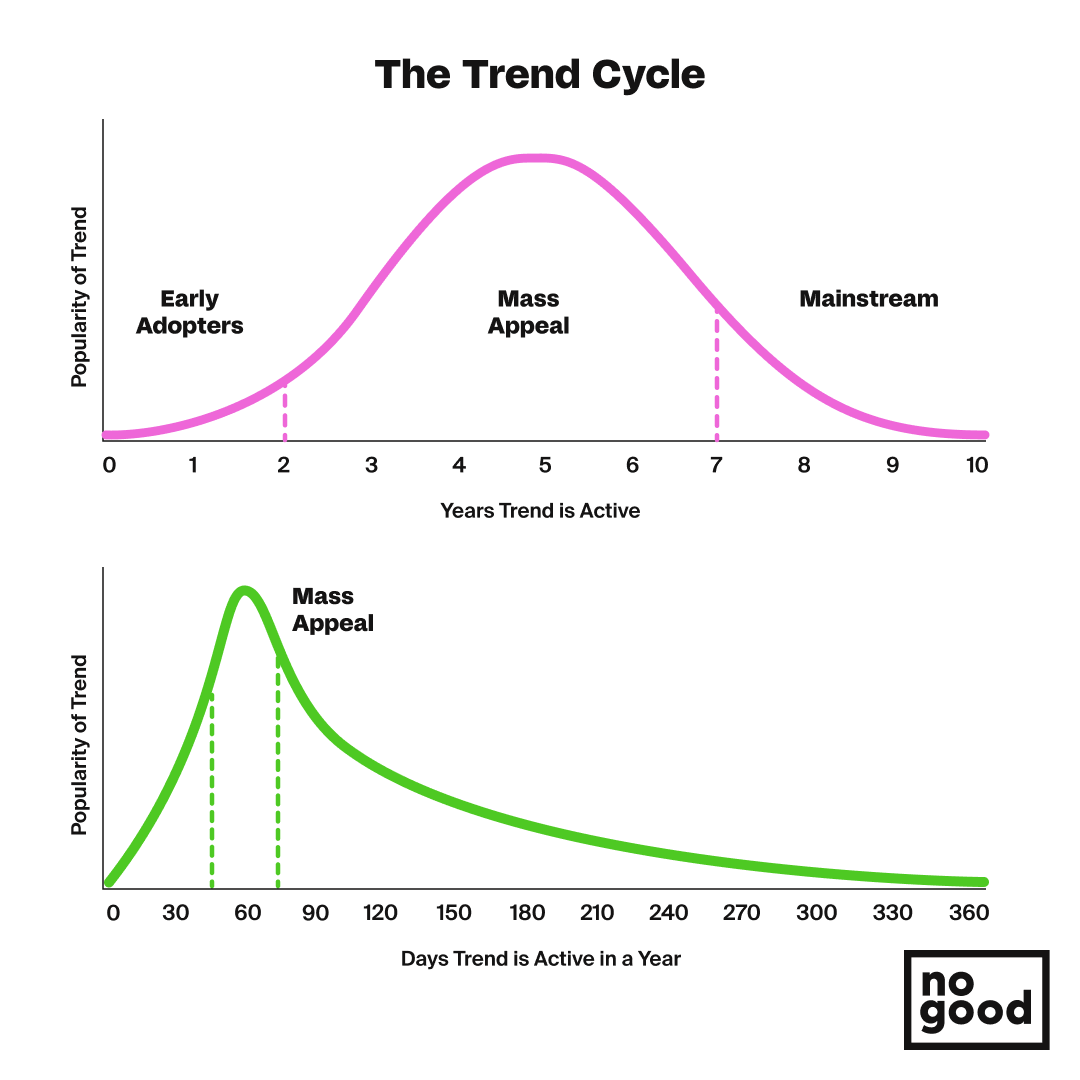

As most trends tend to ebb and flow between their aesthetic limits, similar to the way that iOS went from a user interface that was driven by depth, to being dominated by flat design, and then back again, the recent rejection of perfection in content is more so a logical next step than a radical shift in current trends.

While Instagram had nearly a decade of control over the social media landscape, with influencers and brands perpetuating content that portrayed an idealistic perception of lifestyle and product, there are only so many pristine fit-pics that one generation can handle. And as the lines between content and advertising continued to blur, communities of consumers became increasingly skeptical of the lofty promises being made through content, as unsurprisingly, the reality did not often match up with the expectations. As social shopping became the norm, and the start-up boom of the same decade picked up speed, communities of consumers were increasingly met with disappointment when their social impulse buys arrived at their doorstep and they didn’t experience the radical shift in lifestyle that the product had seemingly promised by way of its aesthetic.

The once glorified and sought-after aesthetic of all things deemed “Instagram-worthy” was a by-product of a number of things:

- Venture capitalism + Red Antler Brands

- Technological advancement + Production Accessibility

- Influencers

Let us explain:

Venture Capitalism:

The startup boom was largely driven by venture capital, a form of private equity where individuals or groups of individuals pooled capital in order to fund business ventures. Direct to Consumer brands, mainly those of the Red Antler variety, rose immediately to prominence with their trendy aesthetics, healthy advertising budgets, and cutting-edge business models (at least for the time).

Unsurprisingly, the success of brands like Casper, with their instantly recognizable packaging that could be seen dotted across any major city, Snowe whose clean aesthetic reflected many millennial dreams of owning a brownstone in TriBeCa, and Brooklinen with its promises of luxury levels of quality at an attainable price point, lead many new ventures to believe that they had cracked the code to success in the modern social era.

What followed can only be described as a decade of brands driven by what we’ll call the Red Antler look, operating under the assumption that the key to the success of these brands was not the ad dollars being spent and allocated via venture capital, but rather the branding and visual treatment that they were representing in the media — not the case.

This aesthetic was paired with a lifestyle component with these brands which extended beyond social media and directly to the consumer (redefining DTC). Mattresses from Casper weren’t JUST selling a comfy mattress in a box, they were selling the “full sleeping experience.”

The combination of these factors culminated in the prevalence of lifestyle chasing that became synonymous with Instagram as a platform, as well as the content created for it, and the brands that were attracted to it as venture capitalists put money behind emerging brands — further saturating the market and the platform with Instagram-worthiness.

Technology and Production Accessibility:

While in 2020 Lady Gaga did shoot an entire music video on an iPhone 11, the previous decade saw a major leap forward in regard to access to what would have previously been considered “production level” equipment.

While digital SLRs like the Canon 5d Mark II were priced at around $3k when initially released in 2008 and were widely considered “professional” equipment, by the period that Instagram was being fully leveraged as a marketing platform by brands the barrier to entry to produce high-polish content had been significantly lowered as camera sensors became cheaper to produce, providing access to more accessible equipment, and the second-hand market for DSLRs provided opportunities for personal ownership at a higher rate.

This increased accessibility paved the way for creators to shoot in HD, capture images at high resolution, shoot in RAW, and otherwise harness a level of production quality that would previously cost thousands of dollars, all from the comfort of their homes, or the day-rate at a local studio.

Influencers:

This combination of high budgets and accessibility to high-production equipment created the fertile ground that ultimately gave birth to the rise of the influencer.

Unlike the content creators of the present-day (more on them in a minute), the era of the influencer took place during a period when Instagram was still very much all about the square photo. This nurtured a culture of brand collaborations that relied heavily on, if not exclusively, perfection – or the perception of such.

It’s important to note that this came at a time when, for the most part, brands hadn’t yet fully adopted the practice of having full media teams in their employ, and content strategies were generally limited to a single post a day.

These limitations, if self-imposed, gave flexibility to production during the time of chronological scrolling, so brands had the opportunity to gain a following and have their content be displayed immediately in front of their audiences – once a day.

The results naturally became a race towards inaccessible portrayals of perfection in both aesthetics and lifestyle, as influencers were given influence due to (in most cases) pre-existing affluence, and their ability to align products with their aspirational lifestyles. The pristine imagery of the age of influencers was more a byproduct of the time’s social media best practices, as attention was easier to grab and there was far less competition for it – with users being quickly swayed with much more than pretty pictures.

How it’s going

While TikTok was growing alongside many of the Red Antler, Millennial aesthetic brands that gave rise to influencer culture and the “Instagram-worthy” aesthetic, it was only in the past few years that it truly became the juggernaut that we know it as today.

In turn, the picture-perfect practices that were once dedicated to crafting the most eye-dazzling single image that would be published on a daily basis have been replaced by those that have become synonymous with authenticity – and for good reason. While technology has arguably advanced further and producing high polish content is easier and more accessible than ever, the cadence at which content is produced has increased exponentially leading creators to focus on the now, giving more insights into themselves, their style, and their true selves.

The authentic aesthetic is equal parts:

Let us explain:

A cultural paradigm shift:

While it was easy to be enamored by the beautiful images that plagued Instagram feeds for the mid-late aughts, calling them inauthentic would not be an inaccurate description of a lot of the content being produced for the platform at the time.

As the expectations for lifestyle grew loftier and loftier with the addition of celebrities to the content mix, so came with it a number of new services and insider tips and tricks that further blurred the lines between lifestyle and reality.

With services like Rent the Runway and Airbnb entering the market, it quickly became a matter of budgeting and production in order for influencers to quickly fabricate a lifestyle that was maybe not their own for the sake of selling products in their feed. And while those services weren’t created with the express purpose of making influencers look good, there were a number that were. Companies began entering the production space to offer influencers access to private jets, staged clubs, and other lifestyle signifiers that they could rent, sometimes by the hour, in order to show up, snap a pic, post, and get paid – not very authentic.

As millennials aged up and priorities shifted as they began advancing their careers, building budding families, and otherwise aging out of the allure of their own eponymous aesthetic, GenZ quickly became THE it generation for brands and marketers to obsess over.

As is true with most new generations, GenZ had (and has) a unique perspective on what is and isn’t important, what they like to see in media, and how they taught brands and advertisers to communicate with them.

Authenticity was at the core of these teachings, as the new generation sought peer validation over brand narrative, realistic representation of product and life, and less focus on the ideals of perfection as body positivity, inclusivity, and diversity became to GenZ what affluence was to millennials.

A production requirement:

With the shift towards short-form video over still images, and the TikTok algorithm favoring trendiness and timeliness above all else for the sake of virality and discoverability – perfect was no longer an option.

Media plans of today, while still likely incorporating a post of some sort for their Instagram feeds, are heavily favoring short-form video as the format of choice. And while the accessibility for production-worthy equipment has become drastically higher, with most households having a ring light and smartphone combination somewhere within them, turnaround time is now a factor in winning or losing with content.

Despite how far smartphones have come in their ability to make editorial quality images, the rate at which content is not only expected but necessitated to be produced does not allow for the high polish standards of the social media generation’s past.

As trends fluctuate and change within a more rapid cycle, and TikTok’s algorithm favors those who are posting multiple times a day, many brands and creators still trying to meet the expectations of their communities to maintain a presence in a cross- or omnichannel capacity, there simply isn’t the time or justification for polish. While yes, a trendy lipsync video may require multiple takes, and adding and editing onscreen text may take time, each day’s output is no longer the grand plus that it once needed to be. For TikTok specifically, content recall, due to the rapid pacing of trends, and focus on discovery rather than a strict focus on followers, is a secondary metric as compared to grasping for virality and moving quickly to the next trend.

Note how polish and perfection were not mentioned in the focus for TikTok content in this new high-output landscape. Authenticity of content comes from not only the inability to hide imperfections due to lack of time for editing and retouching but also from the expectations that creators and brands will show up – and always as their best selves.

The shift here is that the “best self” is whoever that creator happens to be on any particular and however they are as well. The trends rest for no one, and communities have prioritized supporting each other over all else, even if it’s a less-than-ideal day for that person.

An actual aesthetic:

If the aesthetic of authenticity weren’t just that, an aesthetic, then we would probably call it by another name. And to be honest it is totally a look and one that has grown organically (and authentically) from the above cultural climate conditions.

The rawness of the aesthetic comes from, as we mentioned, showing up as your best self, whoever that self may be at that particular time. And while beautytokkers may be sharing their daily routine on camera, they’re certainly not doing it with a first-pass face full of product to hide their imperfections.

And the cadence at which we show up is only further supported by the look of being spontaneous, natural, and authentic. Scroll long enough through your for you page and you’ll see people crying in their car, dancing in class, lip-syncing with their grandma, or lounging in their leisure clothes – and that’s fine.

The aesthetic of authenticity is quite literally the opposite of what it meant to be “Instagram-worthy” because it rejects the notion that being otherwise is to be not worthy, and the new aesthetic thinks that’s kind of bullshit.

So, yes. You may see ring light highlights in the eyes of a content creator, or they may be putting on foundation, or they may be trying to portray a flattering image of themselves, but there’s no shade for those who don’t – and that’s a look.

Brands, but make it authentic:

While many brands have been struggling to adapt to this new aesthetic of authenticity, the honest reality of the situation is that they don’t really have too much of anything – it’s kind of the beauty of the whole movement.

While before, productions required multiple people to spend multiple days at a studio or on location with call sheets and shot lists and all these things, while those practices aren’t necessarily “dead” they’re definitely not thriving in the same way they once were. Productions are now happening on a micro scale, across multiple communities by way of content creators who collectively span industries. That collection of content creators is now the aesthetic of the brand more so than any brand treatment, guidelines, or formalization of a brand.

Hear us out.

Leading by example, as we strive to do, if you were to look at our content on TikTok, Instagram, or even our Blog, while it is consistent, the “brand” is really the people behind it.

Watching multiple TikToks, you’ll see multiple faces, and experience multiple flavors, and it’s those multiple flavors that come together to make the exquisite TikTok souffle that is NoGood’s content. Each individual is its own spice, and really a key component to our brand, and it’s the culmination of those components that make our authentic aesthetic.

Yes, we have brand colors, and we have fonts. But they, for all intents and purposes, very much do come secondary to the main attraction of our brand – which is our people.

This translates directly to our blog as well, where you may notice this piece droning on and on and on, while others are concise and to the point, and others still are listicles, brand guides, or growth strategies for prominent brands.

You may further notice that each is written with a unique tone and cadence and that there’s no restriction on the writing to encapsulate or distill an essence that can be considered the “NoGood voice.” There are gentle guidelines, like the brand guides, which steer our people in certain directions, but it’s their thoughts that make up the content and their voice that makes it NoGood.

So for any brand, looking to be deterministic about what the “authentic aesthetic” looks like or sounds like or feels like, it may be time to take a small step back and look at the larger point, and possibly inward.

If your brand is true to itself, and the people you work with are true to the brand, and they are just as much the brand as you are and the content they’re producing is themselves, then the content they’re producing is the brand and the brand is achieving the aesthetic.

That’s a wrap

As we navigate the landscape of authenticity, and as brands look more and more to leverage the new way of not only looking but thinking and communicating, it’s important to understand that, unlike a brand guide, there aren’t necessarily key features to what it is to be authentic – and that’s kind of the point.

While some brands have tried emulating authenticity through productions meant to mimic UGC, modern audiences know better.

While the aesthetic of authenticity may be perceived as being low polish, or a torn t-shirt, or a messy bun while recording a trend, it’s more than just a look.

For as frustrating as it may be to hear, “You’ll know it when you see it.” It’s honestly true. Authenticity can’t be bottled, it can’t be distilled, and it can’t be sold. It can only be identified, curated, and collaborated.